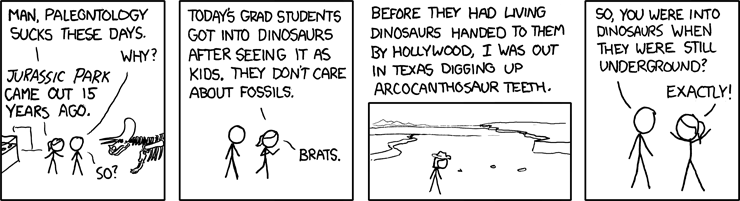

(http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/460:_Paleontology acessed on 7/14/15)

(http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/460:_Paleontology acessed on 7/14/15)

There is no denying that interest in macrofossils partially stems from how aesthetically pleasing (or interesting) they are. However, microfossils are incredibly easy on the eyes as well... as long as the light on your microscope isn't on a blindingly bright setting. This week we will be highlighting some of our most beautiful Foraminifera and Ostracods, as well as the Computed Tomography scanning that is used when we want to explore internal structures. Because beauty isn't only test deep, right?

Elphidium fax fax, a paratype associated with David Nicol's publication titled "New West American Species of the Foraminiferal Genus Elphidium", published in the Journal of Paleontology, 1942.

Elphidium fax barbarense, a paratype associated with David Nicol's publication titled "New West American Species of the Foraminiferal Genus Elphidium", published in the Journal of Paleontology, 1942.

Tuberitina bulbacea, a holotype associated with Galloway and Harlton's publication titled "Some Pennsylvanian Foraminifera of Oklahoma, With Special Refrence to the Genus Orobias", published in the Journal of Paleontology, 1928.

Bairdoppilata pondera, our beautiful Ostracod this week, is a holotype associated with Jenning's publication "A Microfauna from the Monmouth and Basal Rancocas Groups of New Jersey", published in the Bulletins of American Paleontology, 1936.

Elphidium cynicalis, a holotype associated with Jenning's publication "A Microfauna from the Monmouth and Basal Rancocas Groups of New Jersey", published in the Bulletins of American Paleontology, 1936.

Cibicides burlingtonensis, a holotype associated with Jenning's publication "A Microfauna from the Monmouth and Basal Rancocas Groups of New Jersey", published in the Bulletins of American Paleontology, 1936.

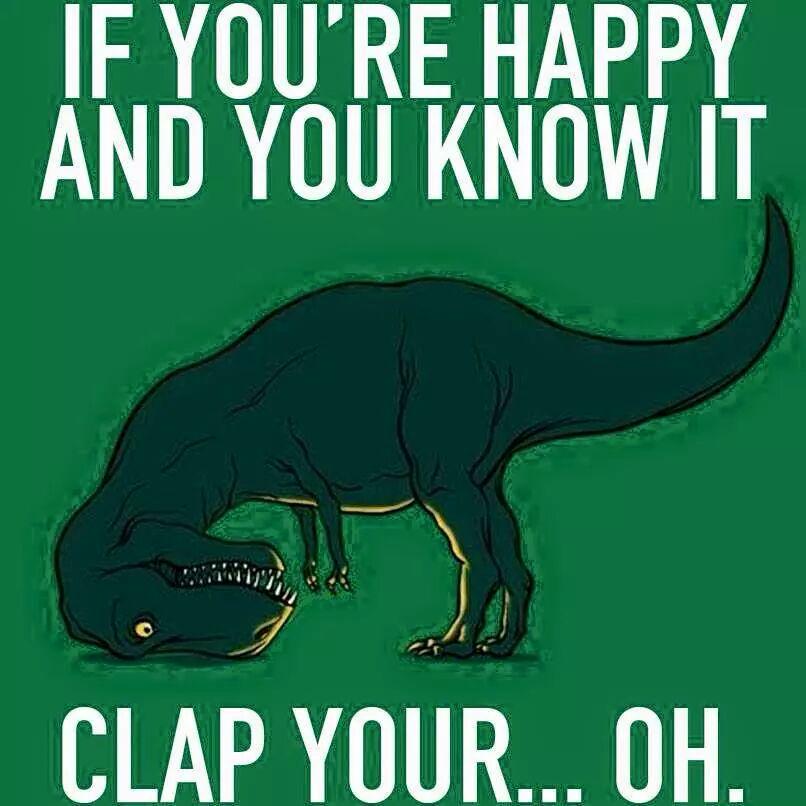

Aren't they pretty? Give them a round of applause! Or at least try..

(https://pbs.twimg.com/media/B9nWTuCCcAAoStA.jpg acessed on 7/14/15)

So what happens when we want to see beyond the external structure of a specimen? Luckily, here at the museum we are equipped with a CT scanning machine, or "Computed Tomography", which translates to the imaging of objects by sections with the use of a penetrating wave. A CT scanner bombards an object with x-rays as the object rotates around a central axis. As the object rotates, thousands of images are collected from all angles, which are then compiled to create a 3 dimensional reconstruction of the object. This allows us to see beyond the surface of a specimen!

Below is an image of a project that intern Lindsay Walker is working on. She is finishing up the reconstruction of Foraminifera Guadryina from Diamond 1928, an unpublished master's thesis.

You can see in the lower right corner of the screen capture that the scanning of the image allows us to see the different chambers of the organism, all without having to do any physical opening of the specimen.

Below is intern Claudia Deeg completing the reconstruction of

Epistomina flinti, a holotype specimen from Galloway and Wissler's publication titled "Pleistocene Foraminfera From the Lomita Quarry, Palos Verdes Hills, California", published in the Journal of Paleontology, 1927.

Last but not least, intern Morgan Black completed a reconstruction of holotype specimen Cythereis tremoidia, from R.A.M Schmidt's Columbia University Master's Dissertation, titled "Miocene Ostracoda from Yorktown Formation Virginia", published in 1939. Below is a video of the final product.

Not only are these microfossils useful, but they sure are good-lookin'!

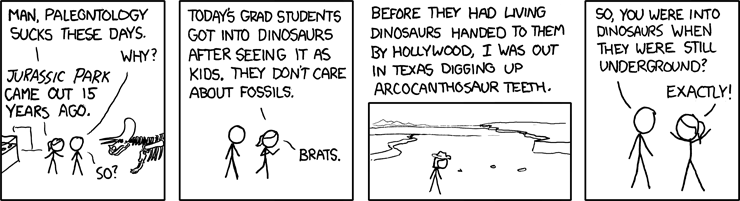

(http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/460:_Paleontology acessed on 7/14/15)

(http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/460:_Paleontology acessed on 7/14/15)