|

| Morgan was thrilled to have worked with Ellen for eight weeks |

Early on, Ellen was interested in the sciences, but thought about chemistry and biology, not geology or paleontology. Then she went to Utrecht University (The Netherlands) information days in 1968 to look at options in the sciences, and was told that women do not study geology. That was the fire and drive for her to decide to become a geologist. She never looked back, earning a bachelor’s and master’s degree in Geology, then a Ph.D. studying benthic foraminifera. For the next 35 years or so, Ellen has studied microfossils to make major advances in the field of paleoceanography, which eventually led her to the AMNH. To us interns, Ellen is the "foram expert" and we take every Tuesday to absorb her knowledge and admire her passion for the historic foraminifera and ostracod collections for the benefit of future scientists.

|

| Sam and Bushra enjoying the spectacular view over Central Park West. |

Travelling with her father in the northwestern parts of Pakistan developed Bushra's love for mountains and nature. However, it was not until she got involved with rocks, minerals, and mapping at the University of Karachi did she passionately pursue her Bachelor's and Master's in Earth and Environmental Sciences while being the only woman to graduate in the top 10 students of her class. Immigrating to the United States in 1984, Bushra found a job working as a research assistant at Lamont Doherty Geological Observatory. She eventually ended up working at the AMNH as a Senior Scientific Assistant and has been managing the Fossil Invertebrate collections since 1997. We all consider Bushra to be kindhearted, patient, understanding, intelligent, and witty. She has shown all the interns what it means to be a respected professional and mentor.

Today, four more female trailblazers have made their mark at the AMNH. Lindsay, Morgan, Brittney, and Claudia each have bright futures and inevitably will rise to the top of their respected field of study. It has been a pleasure to work with all of them.

|

| Acknowledged invertebrate paleontologists on the steps of the AMNH during the early 1900s and today's stars making their mark 100 years later. |

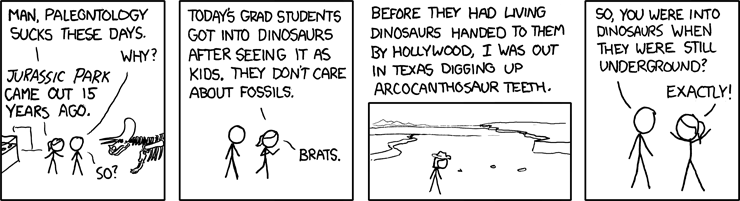

(http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/460:_Paleontology acessed on 7/14/15)

(http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/460:_Paleontology acessed on 7/14/15)